SOBC Spotlight: Interview with Eric Loucks, PhD

In this Spotlight feature we focus on Eric Loucks, PhD, Associate Professor in the School of Public Health at Brown University. His SOBC research investigates the effects of mindfulness training on blood pressure reduction by investigating aspects of self-regulation as targeted mechanisms of change. This work has the potential to inform our understanding of mechanisms underlying the successful reduction of hypertension risk.

In this Spotlight feature we focus on Eric Loucks, PhD, Associate Professor in the School of Public Health at Brown University. His SOBC research investigates the effects of mindfulness training on blood pressure reduction by investigating aspects of self-regulation as targeted mechanisms of change. This work has the potential to inform our understanding of mechanisms underlying the successful reduction of hypertension risk.

Q: As you know, researchers define mindfulness in multiple ways, and even among scientists who do agree on a single definition, mindfulness is nevertheless typically agreed to be a multifaceted construct. One common definition involves, for example, present-moment awareness as well as an attitude of acceptance. Additionally, interventions aiming to improve mindfulness often vary in their instructional and procedural details. How did you design this particular intervention in order to enhance aspects of mindfulness, and what are participants asked to practice, how often, and for how long?

Dr. Loucks: We designed the intervention grounded in an evidence-based mindfulness intervention delivered in health care settings called “Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR).” Some of the formal mindfulness practices we use that are specifically designed to improve mindfulness are sitting meditations focused on breath awareness, body scans that bring non-judgmental awareness to each part of the body noticing sensations in this moment, and mindful movements that are based in a gentle hatha style of yoga. With the mindful movements, the most important focus is bringing mindful awareness to thoughts, emotions and physical sensations associated with the movement – this is more important than the posture itself. Participants go through this 9-week program that meets once a week for 9 weeks, as well as attending an all-day retreat. They have about 45 minutes of recommended mindfulness practice to do at home each day, including about 30 minutes of guided mindfulness practice. Interestingly, we are seeing that the one-third of participants who do the most mindfulness practice at home have about 10 mmHg lower systolic blood pressure through to 12 months follow-up, compared to the one-third of participants who practiced the least. It seems similar to watching my daughters practice their piano and violin – their skills definitely advance more quickly when they are practicing more.

Q: As you summarized in the 2018 SOBC Annual Meeting, mindfulness training has been shown to engage processes related to emotion regulation, interoception, self-compassion, and attentional control. Which of these potentially mediating mechanisms of the intervention are most likely to be implicated in any observed benefits of mindfulness on lowering blood pressure? Might multiple mechanisms work together to achieve their effects (e.g., using increased attentional control resources to regulate emotions more effectively)?

Dr. Loucks: We hypothesize that all of these mechanisms are involved in the intervention, and we hope through the UH3 funding phase that we will be able to analytically answer this question. Our qualitative interviews suggest that participants’ interoceptive awareness (i.e. awareness of their thoughts, emotions and physical sensations) is being heightened. Participants have been sharing that the improved self-awareness is helping with detecting themselves being stressed earlier on in the stress reactivity process, and then apply some of the emotional regulation tools to then be more successful reducing the stress reactions when they happen. Participants are also reporting that the interoceptive awareness is helping them be more attuned to how they feel when they eat healthy/unhealthy foods, and when they exercise, leading them to engage in the healthy behaviors more. If we are funded to advance to the UH3 phase, the study is designed to perform mediation analyses to quantitatively answer this question.

Q: Impressively, the mindfulness training has been associated with effects lasting 12 months after the start of the study. Specifically, participants completing the intervention showed reductions in self-reported difficulties in emotion regulation, increases in interoceptive awareness, and improved sustained attention in a behavioral task. In the case of the findings about emotion regulation and attention, the effects even appear to strengthen somewhat over time. What accounts for these long-lasting effects?

Dr. Loucks: It may be that the mindfulness interventions provide participants with tools and practices which they can continue to apply long after the course is done. We wonder if this is the case particularly for the emotion regulation domain, where difficulties in emotion regulation continued to decline through to 12 months follow-up. In this program, participants also have access to community and resources after the 9-week course is done. These include invitations to all-day retreats that happen 3 times per year, attending a community group that meets twice a month in-person or online, and access to a website that provides fresh recordings and talks from the community groups. Honestly, not that many participants seem to use these resources (maybe 20% or so), so it may be the tools gained in the course are continuing to be used after the course is done to foster lower blood pressure.

Q: A core principle of SOBC is that self-regulation is important for health behaviors. We know that medical treatment adherence and other health behaviors, such as diet, are important for blood pressure reduction. What are the roles of health behaviors on the proposed pathway from mindfulness to reduced blood pressure? Might mindfulness promote different health behaviors (e.g., diet, medication adherence) for different individuals?

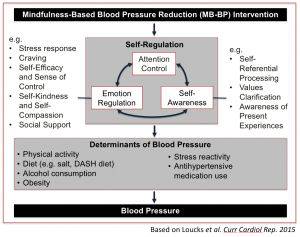

Dr. Loucks: We designed the studies using the SOBC framework, and expect mindfulness to engage with established determinants of elevated blood pressure, such as diet, physical activity, alcohol consumption, stress reactivity, and antihypertensive medication adherence. Our theoretical framework is shown below. We thread this framework into the mindfulness intervention (called Mindfulness-Based Blood Pressure Reduction [MB-BP]), for example by having participants bring mindful awarenesss to their thoughts, physical sensations and emotions during in-class mindful eating of healthy food (e.g. having lunch during the all-day retreat that adheres to the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension [DASH]-diet) or even palatable unhealthy foods (e.g. eating chocolate chip cookies, or bags of chips, during one of the weekly in-class sessions). We do similar approaches with physical activity, where participants are invited to engage in about 20 minutes of walking or jogging if their bodies allow it, bringing awareness to their thoughts, emotions, and physical sensations before, during, and after the physical activity. Almost everyone feels really quite good after physical activity. We all know it is good for us. Yet, most people do not exercise at the recommended levels. Why is this? Often, it is uncomfortable to think about being physically active beforehand, which can affect motivation, or it can be uncomfortable during exercise. Mindfulness training seems to help people become more comfortable with discomfort. It allows us to foster self-awareness so we can customize physical activity to promote positive experiences, noticing which types of physical activity (e.g. group, partner, solo) are most enjoyable, and fostering us to engage with those. We train participants that this moment is influenced by prior moments, including what we ate or drank earlier, or how much physical activity we had. By leaning into these experiences, sometimes insights arise that can shift health behaviors longer term.

Q: Your work is embedded in a larger program of SOBC research with several collaborators who are investigating mindfulness and behavior change. This work involves several largescale projects, including a series of systematic reviews about domains of self-regulation as targeted potential mechanisms of behavior change. How might your current empirical findings be combined with the results of these systematic reviews, or with other empirical findings from other members of the mindfulness research collaborative team, to inform future directions in your program of research?

Dr. Loucks: The systematic reviews show us which self-regulation domains and measures may be most impacted by mindfulness interventions. We can then insert those measures of self-regulation into our studies to see if our specific customized mindfulness interventions change self-regulation. At the same time, the systematic reviews are showing large gaps in objective and biological measures of self-regulation in mindfulness studies, so our interventions can insert new theoretically plausible, validated objective and biological self-regulation measures to better understand the mechanisms by which mindfulness interventions may influence mental and physical health.